Portrature is a recurring theme in Widge’s work.

La prise de portraits est une thémathique récurante dans le travail de Widge.

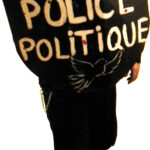

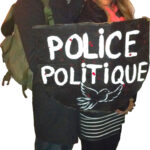

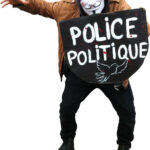

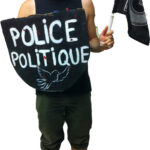

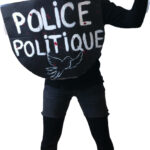

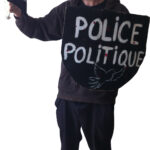

4) Fraternité contre la police politique

Montréal, QC (2015)

This portrait project uses found oppositional artefacts : the “Political Police” shield, a plastic Anonymous mask, a paper mask representing anarchopanda worn to contest bylaw P6, the red tuque of the Montreal Police Fraternity (MPF) and the black flag they often hung from patrol car windows. All were acquired during demonstrations in Montréal.

The (re)mediation and the combination of these four or five oppositional symbols transforms them. Their combination mingles police and political repression of the struggle against austerity and the police to protest against that same.

The MPF tuque is a symbol that blends the Fraternity’s fight against austerity to preserve their pension fund from government cuts, as well as a symbol of police repression. The Montréal police wear this tuque (as well as a variety of camouflage pants) as a pressure tactic, while they kettle protestors and make mass-arrests during Printemps 2015 demonstrations against the same austerity measures they themselves oppose. During the May 1st demonstration in Montréal, I found the MPF car window flag, I later included in the portrait series.

FR

La (re)médiation et la combination de ces quatres symboles de la contestation c’est de les transformer. Leurs combinaison mélange la répression policière et politique avec la lutte contre l’austérité et le droit démocratique de manifester.

La tuque FPPM (Fraternité des policiers et policières de Montréal) est un symbol schizophrénique qui jumelle à la fois la lutte de la Fraternité contre l’austerité afin de préserver ses fonds de pension, ainsi que la répression policière des luttes étudiantes et populaires contre l’austérité. Les policier.e.s portent leur.e.s tuques contestataires en manoeuvrant des souricières afin de faire des arrestations de masse pour réprimer les manifestation du Printemps 2015 (et avant).

Lors de la manif de 1er mai à Montréal, j’ai trouvé le drapeau de la FPPM dans la rue. Maintenant je l’inclus dans les portraits.

Ce projet de portraits photos s’élabore avec des retrouvailles contestataires : le bouclier « Police Politique », un masque Anonymous, un autre masque Anarchopanda contre P-6, la tuque rouge de la Fraternité des policier et policières de Montréal (FPPM) ainsi que son drapeau noir avec le logo de la fraternité accroché des fenêtres des voitures de police. Toutes ces artéfacts contestataire on été aquient lors de manifestations à Montréal.

==========

3) Ici comme ailleurs on a raison de se révolter

Montréal, QC (2013)

On Wednesday, March 13, 2013 during the Masses & Médias 2013 event, I decided to do a portrait series of photographs with the wall of banners on exhibit as a backdrop (see video below). The idea is not original. In fact it’s a ripoff. While hanging more banners from the 13-foot ceiling atop a mobile staircase, two guys walked into La SAT. One of them ran to the wall of banners and stared for a while before standing in front of the one that read “Ici comme ailleurs on a raison de se révolter”. He lifted his left fist into the air, mimicking the banner’s iconography and asked his friend to take a photo. “I’m going to send it out on Twitter,” he shouted back at me as he left. The guy came and went so fast, I didn’t get the chance to ask him about his motivation. I decided to reproduce the initiative at the event.

I invited visitors at the exhibit to stand in front of the same banner with their clenched fist raised to emulate what I had witnessed earlier. No other instructions were given, other than to stand on the ‘X’ taped to the floor. My motivation was to encourage people to interact with the banner and its message in a context other than a street protest and to capture their stance as a new cultural artefact: the photograph. I emailed each portrait to the person(s) portrayed, so they may add it to their personal “shoebox collections” as mediated memories. José van Dijck writes: “Mediated memories are the activities and objects we produce and appropriate by means of media technologies, for creating and re-creating a sense of past, present, and future of ourselves in relation to others.”

The portraits brought the banner from the past into the present as new cultural production. After they are distributed then shared, they have the potential to inspire actions in the future. At least that is my objective.

Each portrait is centred around a banner that was originally used on the streets during protest. At the March 13 exhibit, the banner was de-contextualized from its intended use of leading a contingent during a protest. That night, a group of Cégep students entered the exhibit space and were offended by the display of protest banners. Some of them left, emotionally shaken by the exhibit, one of them apparently in tears. Two of the students stayed behind to seek me out and convey their indignation. “How can you display these banners that are made for the street, some of which I participated in their creation, in a gallery or museum setting, as though the protests were finished!?” I remember pointing to the ‘Mères en colère et solidaires’ banner and telling the students that the woman who takes care of this banner came up to me earlier in the evening to remind me that she needed the banner back by the weekend for a scheduled protest the following week. To the students, the word “archive” was associated with institutionalized memory, museums, capital ‘H’ history and dust. This exhibit was a ritual gathering, a media activism event.

If a demonstration is considered as a performance (one without a script but shaped by ritual) then, according to Victor Turner, activists carrying the banner within a demonstration are in the active “liminal” phase of oppositional performance. The preceding phase, in this context would, include the selection of fabric and paints, the review of potential slogans and the creation of the banner. This leisurely phase, according to Turner, “separates” the activist from the ritual of protest within a preparatory period of collaboration. During the Masses & Médias event activists were in “reaggregation”: a “post-performance” phase marked by a debriefing “cooling down” period, a ritual celebration of past actions that invariably leads to future oppositional performance: a cyclical loop of collective self-renewal.

Each portrait (re)mediates the banner within a new cultural object. Although the banner is the unifying feature of the portrait series, it is no longer the central signifier. The portraits now derive meaning not just from the banner’s claim, but also from each individual’s deliberate and expressive affiliation to that claim. The desire to participate in the portrait series is in itself an oppositional cultural act that will be reinforced when individuals share their portraits with others.

(re)Collected visual artefacts from the 2012 ‘maple spring’ from reserves of posters, banners and protest signs “can be considered markers of cultural agency; it is through these creative rerecordings and recollections that [oppositional] cultural heritage becomes established”. Wendy Chun (p.164) writes that “memory must be held in order to keep it from moving or fading. Memory does not equal storage. While memory looks backward […] to store is to furnish, to build stock. Storage or stocks always looks forward to the future”.

This particular banner — because of the perennial nature of its message — is a powerful source of both memory and stock. It seamlessly unites one protest movement to another and can associate one particularly vigorous period of opposition (like the printemps érable) with the next, due to its inclusiveness.

I suggest that the mashup, sampling and re-circulation of visual artefacts stored in the Artéfacts d’un Printemps québécois Archive will nurture oppositional consciousness provoked during the printemps érable and will affirm an oppositional cultural heritage that will thrive in upcoming justice-based struggles.

==========

2) Vaccination

Lurcuk Village, Tonj North County, Warrap, South Sudan (2009)

After vaccination, each individual receives a piece of paper with their names and a list of the vaccines they received that day. In total, 276 children were immunized for various childhood diseases like measles, tuberculosis, polio, diphtheria, tetanus and 167 women of childbearing years received tetanus vaccines.

==========

1) Student Roles at Sud Academy

Nairobi, Kenya (2009)

The gate of Sud Academy, a school for South Sudanese refugees living in Nairobi, Kenya.

When visiting Sud Academy after my return from South Sudan, I showed the students photographs and video I’d taken during my visit there. I asked the students if I may take their portraits focussing on their official roles at the school. Below are the photos of the students that accepted my proposal.